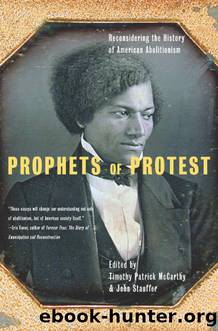

Prophets of Protest by Timothy Patrick McCarthy

Author:Timothy Patrick McCarthy

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781595588548

Publisher: The New Press

Understanding Black Responses to Racial Science

The reality was, as is often the case with the past, likely to be more complex than historiansâ questions permit it to be. There were many sorts of relationships between black protest thought and the discourse of race, just as there were multiple consequences to black thinkersâ engagement with that discourse. It makes sense, then, to forgo conclusions applicable to all black thought, and focus instead on the myriad possibilities created by the shifting relationship between racial protest and racial science.7

Eschewal occurred when black thinkers simply failed to respond to the arguments of racial science. Evidence for this is found in the innumerable extant sources by African Americans that simply did not directly address the claims of racial science. African Americans spoke and wrote about hundreds of topics; racial science was only one of them. Students of antebellum black thought should be struck first with the infrequency with which black thinkers set out directly to refute the claims of antebellum racial science. For African Americans, the threat posed by scientific ideas of race paled in comparison to that posed by popular forms of prejudice such as blackface minstrelsy, proslavery arguments that were not scientific but religious or economic, the alleged indifference to racial uplift of too many of their own people, blacksâ declining status in law and constitution, racist mob behavior, and a host of other concerns.

Of course African Americans did acknowledge the threat posed by antebellum racial science, and did not hesitate to challenge it in myriad ways. The next highest level of engagement with the discourse of racial science was dismissal. Dismissal occurred when African Americans acknowledged the existence of scientific racism, but consciously refused to dispute its claims. A classic case of dismissal occurred in 1808, in an essay by an anonymous member of the African Society in Boston. Considering the question of âwhether the Africans ought be subject to the British or Americans, because they are of a dark complexion,â the author dismissed the producer of such arguments with contempt, writing: âWe believe them to be so trivial, so fallacious and groundless, that we think he must have so hard a study to support it, that we think we had better postpone hearing his objection until some future period.â8

But of course the discourse of racial science did not die of neglect. As arbiters of cultural power and legitimators of popular ideas, African Americans simply lacked the power to consign racial science into oblivion. This is a powerful counterpoint to those scholars who prize the ideological autonomy of the black working class or the enslaved. Dismissal works best when wielded by those with potent cultural authority. African Americans who practiced it, by permitting hostile speech to go unchallenged, threatened to legitimize racist thought through silence. As theories of polygenesis began gaining new credence in the 1820s, instances of dismissal declined. By the late 1830s, racist arguments that were once beyond sufferance seemed to demand pamphlet-long refutation. As early as 1827, David Walkerâhardly an ideological collaboratorâargued for the necessity of engaging racist discourse.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| United States | Abolition |

| Campaigns & Battlefields | Confederacy |

| Naval Operations | Regimental Histories |

| Women |

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3380)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(3178)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2896)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(2374)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(2223)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2202)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(2156)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(2136)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(2102)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(2097)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1987)

Being George Washington by Beck Glenn(1941)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1928)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1803)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1694)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1687)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1672)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1666)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1648)